OTB & Hierarchies

The Difficulties, Vagaries, and Headaches of Demand Forecasting

Open-To-Buy is a simple concept at the macro level. It’s buying inventory in support of a reasonable sales expectation. But OTB can very quickly become agonizingly difficult to manage over a broad assortment of products. Ideally, OTB wants to be as data driven as possible. But…different products have different shelf lives and the sales data on those products have different shelf lives. And the Time/Action calendar to place initial buys and then reorders have different lead times. So the simple macro concept immediately becomes very complicated at the micro level. Let’s look at the details of “WHY?”

For the purposes of this article, Open-To-Buy is defined as the process of determining the quantities of various products that need to be designed, ordered, and manufactured within the bounds of reasonable sales expectations and the supply chain’s Time/Action calendar. This is not about replenishing store stocks with already manufactured products sitting in the warehouse. That’s a separate process that happens downstream from OTB calculations. That inventory and its various rates of sale become part of the overall OTB calculation. The job of the OTB calculation is to establish parameters and boundaries, category by category, risk level by risk level, given the vagaries of demand forecasting and the downside risk and margin exposure of overbuying. There is a push/pull dynamic at work. Maximize sales upside while minimizing (optimizing) inventory levels and potential margin downside.

OTB calculations are built on the ideal world premise of always being able to offer the customer 5R content:

The…Right PRODUCT

at the…Right PRICE

at the…Right PLACE

at the…Right TIME

in the…Right QUANTITY

AND, execute optimum seasonal conversion with minimal end-of-season residue inventory. This entails giving due consideration to a broad array of variables, along with regional and store specific requirements.

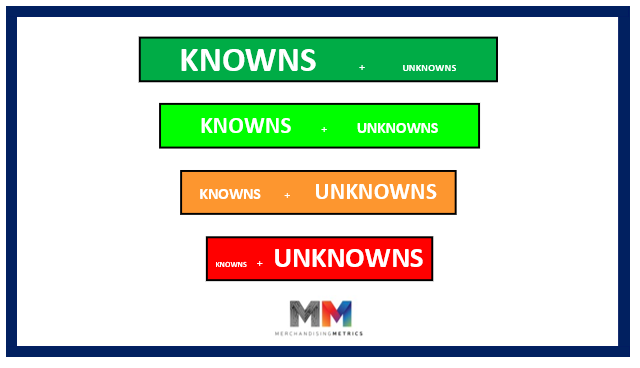

In order to accomplish that, we need to consider that not all data is created equally. It might best be described as a hierarchy of Knowns and Unknowns, as depicted in the graphics above and below.

There is a hierarchy in the levels of RISK in different products.

There is a hierarchy in the levels of FASHION in different products.

There is a hierarchy in the levels of SEASONALITY in different products.

There is a hierarchy in the levels of REPLENISHABILITY of different products.

There is a hierarchy in the levels of REGIONALITY of different products.

There is a hierarchy in the levels of STORYTELLING in different products because…

There is a hierarchy in the levels of DIFFERENTIATION and DISTINCTION that different products bring to the STORY.

There is a hierarchy in the levels of SHELF LIFE of products.

There is a hierarchy in the levels of SHELF LIFE of data.

There is a hierarchy in the levels of KNOWNS and UNKNOWNS.

There is a hierarchy in the COMPLEXITY OF THE SUPPLY CHAIN for each product.

There is a hierarchy in the COMPLEXITY of different TIME/ACTION CALENDARS.

There is a hierarchy in the MANUFACTURING EFFICIENCY of the different products.

There is a hierarchy in the levels of PROFITABILITY of different products.

All these different hierarchies, these graduating scales of Knowns and Unknowns, mean that there are wildly varying levels of predictability within the full assortment of products. And OTB is built on predictability. If the OTB calculation is for 1-2 months out, then current trends can provide solid predictability across the full range of products. If the calculation is for 6-9 months out, then there is going to be a wide range of predictability across the range of products and their risk levels.

When we take into consideration the range of predictability across the breadth of variables that go into OTB, it becomes immediately apparent that OTB calculations are not as purely data driven as we would like to think. In fact, there is some level of outright guesswork involved. Informed and educated guesswork, but guesswork none the less. No one likes to say that out loud, because the whole point is to be as data driven as possible. But the fact that both product and data have variable shelf lengths means that there is a lot of subjectivity involved in the OTB calculation process.

The graphic above summarizes it all by saying that the more basic products and key items are more data driven (more data + longer shelf life of that data) and more predictable. Fashion products by their very definition are less data driven and any current sales data has a short shelf life. Shorter than most Time/Action calendars can handle. (A couple of ecommerce businesses are in the process of proving otherwise.)

Some product categories might not have a lot of hierarchical variables. I imagine that much of the CPG world has a fair degree of stability and predictability. But everything in the apparel business is hierarchical. Everything. So OTB at the macro level is necessary to establish boundaries, and then obviously it needs to go deeper. But even at the department level, that's just a lower level macro of sorts. Somehow there needs to be an accounting for the different levels of fashion, seasonality and shelf life at the style/color level.. And the OTB thought process for Basics won't work for the higher levels of fashion and risk. Those higher levels of fashion and risk need a separate calculation.

Let's face it. The raw math of OTB is not complicated. In fact, the formula is quite simple. It's built on sales, markdowns, and planned, seasonal inventory targets. There are assumptions and predictions for sell-through and markdowns, to be constantly updated on a rolling basis. So, the math, the formula itself, is not the hard part. The hard part is the predictability of all the different moving parts. The hard part is recognizing these different levels of predictability and structuring the OTB calculations accordingly. Different levels of data can drive the calculations of the different levels of product. Some levels of product will have solid levels of predictability at the style level and some levels of product will not have solid levels of predictability at the style level. For products with solid predictability, the manufacturing process can continue at pace. If demand increases, there is some level of cushion built into the planned inventory levels to accommodate a modest demand surge. Same for a demand slow down. In both cases, the pace of manufacturing can be modified, given enough time. For products with limited predictability, the role of the OTB process is to create inventory boundaries so that if demand does not meet expectations, the clearance process does not become a burdensome profit drain. And if demand for some higher risk products exceeds plan, and some styles actually sell out, great!

The limited predictability products are the highest risk products. Fashion. These are the products everybody gets excited about. These are the products that establish and reinforce the brand’s attitude and aesthetic. The fulfillment of the Brand Promise, if you will. These are the products that will fuel all the social media, and the advertising and marketing. BUT…enthusiasm is not data. And enthusiasm for freshly designed products is the intoxicant that often leads to over-buying.

The whole point is that not enough retailers are looking at the hierarchies in their business for the very different levels of risk, data and predictability that are always present. Don’t get me wrong. Risk is a brand’s best friend. So, it’s not about eliminating risk. It’s the differentiator that separates a brand from the competition. That doesn’t mean more is better. That doesn’t mean that a business needs to risk big to win big. It means that the hierarchy of risk needs to be recognized for exactly what it is and managed accordingly. Create and manage risk with eyes open. And OTB is the tool to manage the process.

Jeff Sward

April 24, 2024